Making the Call: Four Factors to Consider When Deciding to Take a Case to Trial

Co-authored by Robert C. Carlson, Pete Fowler, Barbara Laskaris-Lorigan and Ken Kasdan

Publisher in the CLM Construction Claims Summer Edition 2023

When a construction-related legal dispute cannot be resolved by the parties themselves or with the help of a mediator, a party may feel they have no choice but to take the case to trial—either to force an adversary to get serious about settlement or because the party believes only a judge or jury could break the deadlock. Trials are costly affairs, both in terms of the out-of-pocket expenses a party must take on in the lead up to and during trial, and the zero-sum outcomes that often emerge from a trial. To make a smart, informed decision about whether to take a case to trial, a party will need to evaluate several factors affecting their chances of success.

Most of us already know that Trial Evaluation 101 includes considering the strength of the case, potential damages, the costs of litigation, time and resources, and the risks and benefits of settlement. But we, a plaintiff attorney, defense attorney, insurance executive, and construction expert witness with more than 100 years of experience combined, including many trials each, walk through in this article four additional factors we believe have an outsized impact on a party’s chances of success at trial.

Factor 1: What is the fabric of your team?

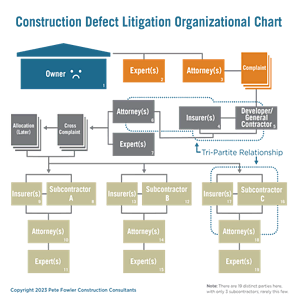

The organizational chart below is a graphical representation of what anyone involved in construction-related litigation knows to be true—litigation brings with it a large cast of characters, each of whom has their own loyalties, strengths, and weaknesses. The chart depicts a small construction litigation matter with only one plaintiff, one direct defendant, and three cross-defendant trade contractors, yet requires a minimum of nineteen distinct parties.

A core aspect of construction litigation trial teams, especially on the defense side, is the tri-partite relationship between the insurer, the insured, and the attorney hired by the insurer to defend the insured in the lawsuit. The complexity of this relationship is well beyond the scope of this article, but depending on the law of the state that governs the lawsuit, an attorney might have ethical obligations to the insurer that come close to, or are equal to, the obligations they have to the insured as their client.

Knowing the law, understanding the quirks of the pre-trial and trial process, and navigating the complexities of a tri-partite relationship are prerequisites for members of a successful trial team. Naturally, the more experienced an attorney, expert, or insurer’s representative is with going through trials—or resolving disputes during trial—the more likely they are to help a party successfully do either.

But knowledge and understanding are only two pieces of the puzzle. To be successful in construction litigation trials where the size of the cast of characters rivals that of a Hollywood blockbuster, team members must be able to handle the stress that comes with trial. Whether it’s an attorney going on little sleep, an expert who was beaten up during cross-examination, or an insurer’s counsel who’s getting fed up with an adversary’s unreasonableness, chances are good that the members of a team will not be operating under optimal conditions.

When that is the case, what is the fabric of the team? Will members of the team maintain their professionalism? Will they stay strong, respectful, and even-keeled? Or will they let their emotions get the best of them, which will prevent them from seeing the situation objectively and using clear, unbiased judgment?

Hopefully, you have sufficient evidence on which to base your predictions about how your team will fare. Years of service do not equal expertise, but the best predictor of future performance is past performance. If you do not have firsthand knowledge of your team members’ past performance, speak with people who have worked with your team members before to inform your predictions.

Your team’s success at trial hinges on both the substantive knowledge and experience its members have, as well as their ability to stay cool under pressure when the trial heats up. In addition, as we discuss below, team members must be willing to speak up and exercise their professional judgment.

Factor 2: What happens when you crunch the numbers?

Your team could be peerless and unflappable under pressure, but if the math of going to trial doesn’t work out, that won’t matter.

Generally—we’ll discuss some exceptions in the next section—plaintiffs and their attorneys will want to take a case to trial when their math looks like this:

(The reasonable and objective value of a claim) *minus* (What it will cost to go to trial (such as attorneys’ fees, expert fees, and other fees and cost)) *minus* (A discount for uncertainty of how a judge or jury might rule given the facts of the case and any unresolved legal questions) *is greater than* (The dollar amount the other side has offered during settlement negotiations).

Defendants and their counsel will crunch the numbers differently and will likely take a case to trial if:

(The reasonable and objective value of a claim) *plus* (What it will cost to go to trial (such as attorneys’ fees, expert fees, and other fees and cost)) *plus* (A premium for uncertainty of how a judge or jury might rule given the facts of the case and any unresolved legal questions) *is less than* (The dollar amount the other side will settle for).

Sometimes, defendants and their counsel might want to tweak their calculations to include a reward of attorneys’ fees and costs, which would lessen their theoretical costs and thus drive down the number on the other side of the equation.

The key to these equations is a set of reasonable assumptions about the value of a claim and the costs and expenses incurred on the road to trial. It would behoove all players to assume worst-case scenarios for valuations and costs so clients and insurance companies are not basing their decisions and guidance on unrealistic expectations.

Factor 3: Are there subjective considerations that override objective math?

Many times, crunching the numbers won’t give the full picture or be the deciding factor in whether to take a case to trial. Instead, the decades of collective knowledge, wisdom, and experience held by the cast of characters depicted in the organizational chart above might guide a litigant toward or away from trial.

In other words, in the professional judgment of a litigant’s counsel, their experts, their insurer’s counsel—and perhaps with defendants, their co-defendants’ counsel, experts, and insurers’ counsel—is there a reason to go or not to go to trial that overrides what the math suggests?

For example, is the trial an opportunity to set a precedent or to send a message to the industry that certain conduct will not be tolerated?

On the other hand, would a settlement avoid a possibly problematic court ruling that could greatly impact industry players, like insurers?

Does one lawyer have the reputation for being a talented litigator, but a horrific trial lawyer, which would motivate the other side to call this lawyer’s bluff, causing them to persuade their client to settle? Or, is the lawyer a well-known lawyer with decades of experience but doesn’t have extensive—or any—trial experience, making them similarly vulnerable to another party calling their bluff?

On the other hand, is one lawyer known to be a clumsy litigator but a skillful presenter who will have the jury eating out of their hands after their opening statement, which might compel the other side to settle before trial?

Even in the absence of these particular factors, is there something about THIS case, THIS judge, or THIS jury pool that might force a party’s hand regarding going to trial? For example, have juries in the jurisdiction recently been willing to hand up generous verdicts against corporations and insurance companies? Or, have juries refused to allow trial lawyers to rile them up and play on their anger with the hopes they’ll return a nuclear verdict?

Additionally, could the case be one where the “winner” could actually lose in the end? For example, perhaps a jury finds a party to have breached a contract, but it zeroes in on a fact that causes it to award the non-breaching party a fraction of the low-end damages the party thought it could secure when it ran the math about taking the case to trial. Or, could a “winning” party face a situation where not only is it awarded a lower dollar amount of damages than forecasted, but then a judge refuses to award that party fees or costs even where it would be common for a judge to do so?

Another consideration is the availability of coverage under the applicable insurance policy with respect to any trial outcome, which the insurer, the insured, and the insured’s counsel should carefully consider, in addition to the costs of trial, when weighing the cost of settlement opportunities. Transparent communication between the insurer and its insured regarding coverage limitations is a must if the insured and their counsel are to properly consider this factor when deciding whether to go to trial.

Money talks, but that doesn’t mean it has to have the last word. Going back to our discussion above about the fabric of a team, team members’ willingness to speak up and exercise their professional judgment, even in the face of math that suggests they do the opposite of what they’re recommending, can be the difference between a mildly unpleasant settlement, and a cataclysmic result at trial.

Factor 4: Have you been managing expectations from the start?

In typical construction litigation, there are two sets of expectations that attorneys and experts must manage in the lead up to trial: clients’ and insurers’.

For clients, their expectations about the probability of success at trial and the cost of going to trial will dictate their willingness to do so. Some attorneys and experts are happy to give their clients ballpark estimates of both, but in our view, the better practice is to break down in plain English and in simple numbers why certain trial outcomes might occur and what exactly the costs of going to trial might look like. Neither analysis needs to be long, but each should be clear.

For example, attorneys should explain why specifically a judge might rule against a client on a question of law, or why a jury might not find the client’s experts as credible as the other side’s experts. Budgets should include both conceivable costs the client will incur and a realistic (if not a bit inflated) estimate of the fees and costs the client might incur if they are on the hook for the other side’s fees and costs.

For insurers, they will probably already know why certain trial outcomes might occur, and will probably provide to a party’s attorney their opinion as to the likelihood of those outcomes happening. But that doesn’t mean they wouldn’t appreciate independent analysis of those outcomes. Additionally, while insurers are well aware of, and honor, their ethical obligation to defend their insured, they’re not big fans of surprises, especially when it comes to trial budgets. They’re going to want to know early and often what the estimated cost is to take a case to trial and why the team wants to incur certain expenses.

But managing expectations isn’t just about providing thoughtful litigation analyses and realistic budgets early on. It is imperative the trial team continually update clients and insurers on the current state of affairs regarding the probability of success at trial and the trial budget. Both frequently change, with scope creep and cost creep coming into play as trial nears. The clearer the line of sight clients and insurers have into the probability of success and the cost to go to trial, the more receptive they’ll be to guidance regarding whether to proceed down that route.

Taking a measured approach through a messy process

Construction litigation cases are almost always messy. The messiest ones are often the ones most likely to go to trial; sometimes because one party mismanaged or misjudged earlier, and now they are stuck “rolling the dice.”

Deciding to press on and take a construction litigation case to trial is a decision that requires parties, their attorneys, experts, and their insurers to first consider the obvious, tried-and-true evaluation fundamentals, and then the more complex and nuanced four “professional judgment” factors we discussed above.

Robert C. Carlson is a founding partner of Koeller Nebeker Carlson Haluck, LLP, based in the firm’s San Diego and Las Vegas offices. His practice areas include Construction Litigation, Auto and Transportation Claims, Insurance Coverage and Related Matters, Pollution and Environmental Litigation, and Employment and Workers’ Compensation Litigation. He can be reached at bob.carlson@knchlaw.com.

Pete Fowler is the founder of Pete Fowler Construction Consultants.

Barbara Laskaris-Lorigan is Vice President – Head of Claims at Golden State Claims Adjusters.

Ken Kasdan is senior and managing partner of Kasdan Turner Thomson Booth LLC.